James R. Noyes, a scholar on the subject, summarizes:

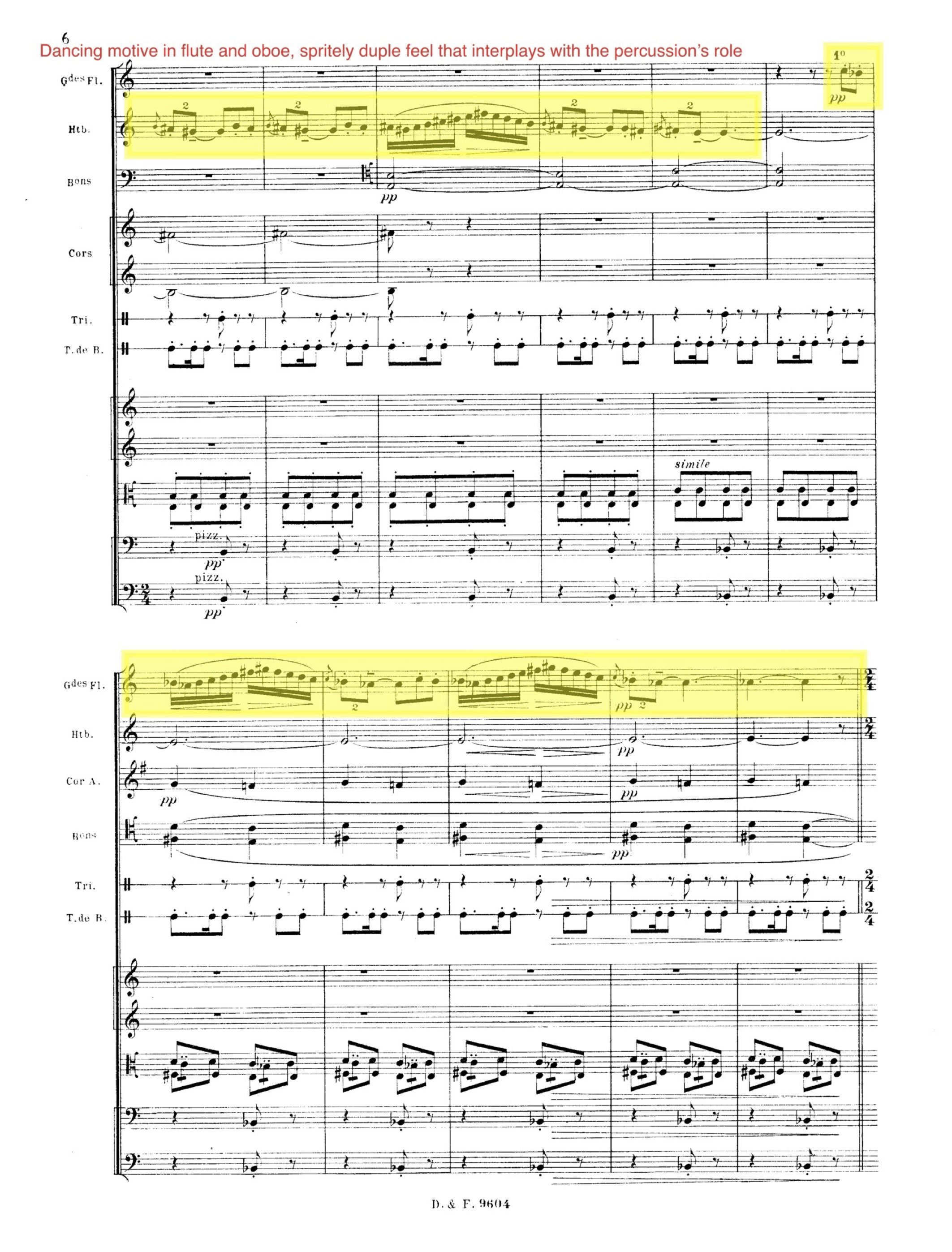

Roger-Ducasse’s orchestral manuscript [MS 1001] incorporates sixty-two of Debussy’s original sixty-five indications, a retention rate of more than 95 percent. Thus, Debussy’s faithful friend remained true to his colleague’s intentions […] To “fill out” the orchestration, Roger-Ducasse created parts for five additional instruments (piccolo, tuba, timpani, triangle, and suspended cymbal) and doubled many of the original lines, scoring woodwinds with the high strings, bassoons and timpani to reinforce the bass, and horns to fill in the middle register, all of which are implied by the Hall manuscript.[17]

In addition to completing the orchestration, Roger-Ducasse also saw to arranging a piano reduction of the work; this is his biggest contribution, more derivative than any of the orchestration found in the full version. Finally, for reasons unknown, the title was simplified to, Rapsodie pour Orchestre et Saxophone (L. 98).

Roger-Ducasse’s involvement with the score preparation and publication of the Rapsodie, unfortunately, has served a platform for musicologists to assume that the work was flippantly composed and never truly finished. This trend was started by Léon Vallas, the first musicologist to write about this work in his book, Claude Debussy et son temps(1932). Vallas wrote that the composition was a “disagreeable task,” “ridiculous,” and “nothing more than a rough draft.”[18] These statements were clearly written in error and do not take into account the actual events that took place throughout the piece’s genesis, development, and prolonged completion. This is made especially evident when one considers the fact that Debussy himself enthusiastically wrote of the saxophone’s “special sonority.” Another blatant error attributed to Vallas’ slanted view is seen when he wrote:

In 1911, [Debussy] again set to work on the instrumentation [of Rapsodie]. But he wrote nothing more than a rough draft on three or four staves, and in this form the work was delivered to Mrs. Hall. [19]

This statement is in error, especially when considering that there is no proof or evidence that Debussy touched the composition after 1903. Instead, Vallas was erroneously referring to the Première Rhapsodie (L. 116) for clarinet and orchestra, confusing the two similarly-titled works. This is evidenced by Debussy’s own writing to Durand in two separate occasions, where the composer misspelled the title of his clarinet Rhapsodie as “Rapsodie,” omitting an “h”. Analyzing the content of the letters finds that he clearly was referring to this clarinet work, especially in a letter from December of 1911, where Debussy specifically discussed the reception of a Russian performance of his recently-orchestrated clarinet “Rapsodie” (misspelled with no “h”).[20] Debussy’s misspellings, combined with Vellas’ misinterpretation of his findings, resulted in a subsequent snowballing of misinformation among musicologists. Noyes succinctly concludes:

Vallas’s “disagreeable task,” became Thompson’s “abandoning the task in despair,” which in turn became “he just could not force himself to the task” according to Seroff.[21]

While Vallas cannot be totally condemned for the publication of his innocent misunderstanding (which may have happened to also verify his personal opinions), it is truly unfortunate that subsequent musicologists chose to base their scholarly writing concerning this piece on the flawed work of another musicologist, rather than approach the work with a fresh perspective via the use of primary documents.

CONCLUSION

At first glance, Claude Debussy’s Rapsodie is beleaguered by several factors, such as the lack of technical virtuosity demanded from the soloist, the complicated series of events resulting in the piece’s development, and the accumulation of negative associations of uninspired compositional flippancy and insignificance at the hands of mistaken musicologists. However, fresh analysis of this work in a modern context, starting with an investigation of primary documents, reveals a new level of understanding as to why the piece continues to be wrongly thought-of and also provides many answers to fill the gaps in knowledge presented by prior scholars. Additionally, it reveals a wealth of new information regarding the development of the piece; including but not limited to the composer’s references to moorish timbres, his integration of French merchant calls, and the nature and extent of the orchestration completed by Debussy and Roger-Ducasse. These aspects of the piece’s development are unique to this composition within the context of Debussy’s canon of works. They also tell a more comprehensive narrative in regards to how the work came to be in its present state. Finally, it reveals perhaps the most important point: this work has too often been portrayed as a flawed concerto, which is further evidenced by a wealth of new editions that transplant orchestral material into the soloist’s part.[22] Alternatively, this piece instead should be approached as an orchestral tableaux that happens to feature the saxophone, serving as a piece to welcome its new timbre to the orchestral winds.

Jean-Marie Londeix, a world-renowned French concert saxophonist and a preeminent scholar on the concert saxophone repertoire, stated that while it is disappointing that Debussy never wrote saxophonists a virtuosic showcase, it does not take away from the beauty of the work; he admits he was mistaken to classify and approach the piece as something it was not.[23] Based on the information accumulated, Debussy likely intended this work to be a nationalistic celebration, representing the voices of his beloved Paris through their inclusion as motivic inspiration, complete with a slightly “mauresque” twist evident in the timbres of his orchestration choices. No other work in Debussy’s cannon can attribute its motives to such sources, making the Rapsodie quite unique in this regard and a one-of-a-kind piece of music. Ultimately, this piece represents a new direction that regrettably did not see more development due to the composer’s untimely death and preoccupation with other aesthetic developments. With these revelations in mind, it is only a matter of time until future scholars must recognize Claude Debussy’s Rapsodie pour Orchestre et Saxophone for the “new direction” that it represents.

FOOTNOTES

[1] William H. Street, “Elise Boyer Hall, America’s First Female Concert Saxophonist: Her Life as Performing artist, Pioneer of Concert Repertory for Saxophone and Patroness of the Arts” (DMA diss., Northwestern University, 1983), 16-17.

[2] William H. Street, “Elise Boyer Hall, America’s First Female Concert Saxophonist: Her Life as Performing artist, Pioneer of Concert Repertory for Saxophone and Patroness of the Arts” (DMA diss., Northwestern University, 1983), 21.

[3] William H. Street, “Elise Boyer Hall, America’s First Female Concert Saxophonist: Her Life as Performing artist, Pioneer of Concert Repertory for Saxophone and Patroness of the Arts” (DMA diss., Northwestern University, 1983), 28.

[4] Robert J. Seligson, “The ‘Rapsodie for Orchestra and Saxophone’ by Claude Debussy: A Comparison of Two Performance Editions” (DMA diss., University of North Texas, 1988), 6.

[5] Smith, Richard Langham, "Pelléas et Mélisande." The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online, Oxford University Press, accessed September 15, 2016, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com.ezproxy.gsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/music/O002420.

[6] Franc Lesure and Roger Nichols, Debussy Letters (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1987), 127-28.

[7] James R. Noyes, "Debussy's Rapsodie Pour Orchestre Et Saxophone Revisited” The Musical Quarterly 90/1 (2008), 420.

[8] François Lesure, Denis Herlin, and Georges Liébert, eds. Claude Debussy Correspondance (1872–1918) (Paris: Gallimard, 2005), 736.

[9] François Lesure, Denis Herlin, and Georges Liébert, eds. Claude Debussy Correspondance (1872–1918) (Paris: Gallimard, 2005), 742.

[10] Franc Lesure and Roger Nichols, Debussy Letters (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1987), 136.

[11] James R. Noyes, "Debussy's Rapsodie Pour Orchestre Et Saxophone Revisited” The Musical Quarterly 90/1 (2008), 422, 432.

[12] Jean-Marie Londeix and William H. Street, "Debussy and the Rhapsody for Saxophone” (video lecture, World Saxophone Congress XVI, Buchanan Theater, St. Andrews, Scotland, July 13, 2012).

[13] Franc Lesure and Roger Nichols, Debussy Letters (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1987), 136.

[14] Jean-Marie Londeix and William H. Street, "Debussy and the Rhapsody for Saxophone” (video lecture, World Saxophone Congress XVI, Buchanan Theater, St. Andrews, Scotland, July 13, 2012).

[15] James R. Noyes, "Debussy's Rapsodie Pour Orchestre Et Saxophone Revisited” The Musical Quarterly 90/1 (2008), 423.

[16] Franc Lesure and Roger Nichols, Debussy Letters (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1987), 158.

[17] James R. Noyes, "Debussy's Rapsodie Pour Orchestre Et Saxophone Revisited” The Musical Quarterly 90/1 (2008), 429.

[18] Léon Vallas, Mare O’Brien, and Grace O’Brien, Claude Debussy: His Life and Works (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1933), 161-62.

[19] Léon Vallas, Mare O’Brien, and Grace O’Brien, Claude Debussy: His Life and Works (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1933), 162.

[20] Franc Lesure and Roger Nichols, Debussy Letters (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1987), 248.

[21] James R. Noyes, "Debussy's Rapsodie Pour Orchestre Et Saxophone Revisited” The Musical Quarterly 90/1 (2008), 417, 418.

[22] Robert J. Seligson, “The ‘Rapsodie for Orchestra and Saxophone’ by Claude Debussy: A Comparison of Two Performance Editions” (DMA diss., University of North Texas, 1988), 9-35.

[23] Jean-Marie Londeix and William H. Street, "Debussy and the Rhapsody for Saxophone” (video lecture, World Saxophone Congress XVI, Buchanan Theater, St. Andrews, Scotland, July 13, 2012).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cottrell, Stephen. The Saxophone, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012.

Debussy, Claude. Esquisse d'une Rhapsodie Mauresque. Paris: Durand & Fils, 1908. Manuscript.

Debussy, Claude. Rapsodie pour Orchestre et Saxophone. Paris: Durand & Cie, 1919. Orchestral score and Parts.

Debussy, Claude. Rapsodie pour Orchestre et Saxophone. Arranged by Jean Roger-Ducasse. Paris: Durand & Cie, 1919. Piano Reduction.

Liley, Thomas, and Stephen Trier. “The Repertoire Heritage.” In The Cambridge Companion to the Saxophone. Edited by Richard Ingham. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Lesure, François, Denis Herlin, and Georges Liébert, eds. Claude Debussy Correspondance (1872–1918). Paris: Gallimard, 2005.

Londeix, Jean-Marie, and William H. Street. "Debussy and the Rhapsody for Saxophone." Lecture video, World Saxophone Congress XVI, Buchanan Theater, St. Andrews, Scotland, July 13, 2012. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hie1vGOl1do (Accessed October 23, 2015)

Miele, Peter. A Comparative Analysis of Three Works for Saxophone and Orchestra. MM thesis, Duquesne University, 1989.

Nichols, Roger. Debussy Letters. Edited by François Lesure. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987.

Noyes, James R. "Debussy's Rapsodie Pour Orchestre Et Saxophone Revisited." The Musical Quarterly 2007, 90/1 (2008): 416-45.

Seligson, Robert Jan. 1988. The “Rapsodie for Orchestra and Saxophone” by Claude Debussy: A Comparison of Two Performance Editions. DMA dissertation, University of North Texas. Ann Arbor: ProQuest/UMI.

Smith, Richard Langham. "Pelléas et Mélisande." The New Grove Dictionary of Opera. Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com.ezproxy.gsu.edu/subscriber/article/grove/music/O002420. (Accessed September 30, 2015)

Street, William. Elise Boyer Hall, America’s First Female Concert Saxophonist: Her Life as Performing artist, Pioneer of Concert Repertory for Saxophone and Patroness of the Arts. DMA dissertation, Northwestern University, 1983.

Trezise, Simon, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Debussy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Trier, Stephen. “The Saxophone in the Orchestra.” In The Cambridge Companion to the Saxophone. Edited by Richard Ingham. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Vallas, Léon. Claude Debussy: His Life and Works. Translated by Mare O’Brien and Grace O’Brien. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1933.